Nov

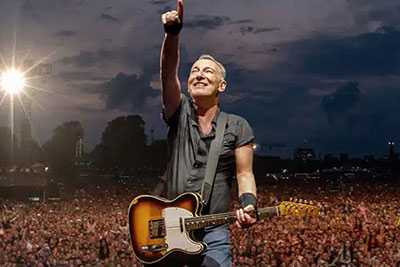

Bruce Springsteen - Cork and Kilkenny gigs sell out in 90 minutes

Kilkenny gig sell out in minutes as Bruce Springsteen fans snap up tickets. The Boss is coming to Ireland in May 2024

Oct

2012

Published on Wednesday 31 October 2012 19:00

Published on Wednesday 31 October 2012 19:00

Cushendale Woollen Mills is the only surviving woollen mill in the South East of Ireland.

The current custodian of the mill is passionate about his craft. When Philip Cushen was just 19 years old his father Patrick passed away, leaving the young man to manage one of the most important craft industries in Graignamanagh.

An iconic brand, it has survived in some form or other since a group of English monks founded an abbey in the town 800 years ago and set up their own mill on the present site of Cushendale Woollen Mills. You can feel the sense of history, place and the past as you enter the building.

The sixth generation of his family to run Cushendale Woollen Mills, Philip has managed to safeguard the future by investing in new ideas and new concepts while remaining true to the way in which the clothes, garments and other wool, lambswool and mohair items are produced.

It is the last mill of its type in the city and county to have survived and many people in Kilkenny city will remember Greenvale and Ormonde mills, which were great employers that are, alas, no more, long since extinct. That makes Cushendale Woollen Mills unique.

The plain exterior of the building does not prepare you for the richness and diversity of what is inside. The old mill once powered by the mill stream, diverted from the Duiske River with its source on Brandon Hill is full of character.

All the machines still work perfectly; some are now used to carry out processes for other Irish woollen manufacturers who have long since dispensed with theirs, only to find they still need them. Cushendale is a special place to be guarded and cherished where a man, proud of his craft and its link with its surroundings, puts quality before quantity as he deals with changing production methods and consumer demands.

All the machines still work perfectly; some are now used to carry out processes for other Irish woollen manufacturers who have long since dispensed with theirs, only to find they still need them. Cushendale is a special place to be guarded and cherished where a man, proud of his craft and its link with its surroundings, puts quality before quantity as he deals with changing production methods and consumer demands.

Many of his fellow weavers have given up and are “out-sourcing”. It may be a good short term idea but in the long term it will mean that certain skills and ways of doing things, passed down through generations, will be lost because the next generation will not have the knowledge and then we will be dependent on imports – making our Irish-produced items extinct.

“They will never produce anything again, that’s it,” he said with authority and a hint of sadness,

Philip Cushen has got soul, real soul. He is passionate about yarns, wool, mohair and keeping alive a way of life, a craft-art form which has been going on around the town of Graignamanagh since the 13th century. The building where the mill stands on the Mill Road, backing on to the Duiske River provides the town with a sense of identity which is almost as important as Duiske Abbey.

He can trace his weaving heritage all the way back to the Flemish weavers who fled mainland Europe in the mid-1600s and came to the South East of Ireland. Indeed some of the Flemish words brought over all those centuries ago are still used by Philip like “stok” - a length of cloth and “skerrin” - the frame on which yarn is placed in preparation for weaving.

He is a lover of language and “dabbles” in many of the European ones and is interested especially in the Celtic tongues.

His energy is palpable and it transmits to those who work with him and have the same passion for the business that he has. You also sense that he has a healthy disregard for those who say there is no future for the textile industry in Ireland. He rubbishes that idea, and says working with wool, weaving and doing other things to the fabrics involved has an artistic side that defines who we are and is worth preserving.

Though the need to create the colours and designs while dyeing the wool to give the rich colours associated with Cushendale is a matter of chemistry, the manner of making the actual fabric is a mechanical process. He asks where else would you find such diversity of challenges in the one job. He wants to find new ways of working with existing fabric to create new lines and breathe new life into the textiles industry to ensure its survival.

When his grandfather was in business, he produced blankets for the local market and was able to make a living so doing.

“My grandfather Philip depended on the people of Graignamanagh for his livelihood. My father had to expand and depended on the markets in Cork, Dublin and especially Waterford for business, while I have to go global, selling to buyers in the US, France, Germany and Japan. However, Irish at home and abroad continue to be our most important customers and this is more than ever the case during these tough economic times when people are coming to recognise and value indigenous Irish crafts. He has embraced new technology and is selling all over the word thanks to his website.

After finishing secondary school, Philip was supposed to go to a textile college in the south of Scotland but his father’s premature death put an end to that. It cost him and he feels that he wasted over 10 years figuring out things for himself, things he could have learned in college in a few years. He is philosophical about it and the fact that he had to graft so hard to learn and keep up with the rest of those in the industry, has stood to him and given him an independence that he might not have otherwise have gained and which now gives him an edge over competitors. However, he did receive a boost with the establishment of the Kilkenny Design Workshops in the late 1960s, set up to help the craft industry locally and nationally.

He recalls with gratitude Kerryman, Mortimer O’Shea being in charge of the textile part of the workshops. “Working there with those professionals gave me an insight into design and products which I would not have otherwise got,” Philip explained.

Luckily for Philip it also stimulated an awareness of old designs which have been revitalised and Cushendale was and is able to capitalise on that.

Not surprisingly, Philip is great with his hands and has no choice because many of the machines are complex and require an intuitive knowledge of mechanics in order to repair them. Not surprisingly, two of his sons are mechanical engineers.

Patrick works on pharmaceutical product lines while Philip, who lives in Belgium, works with Toyota. The youngest member of the family, Michael works with a mapping firm in Dublin. He and Mary, his wife, also have four daughters. Both Anna Maria and Ellen are pharmacists based in Dublin, while Breda is a doctor working presently in Galway. Miriam works in human resources. It continues to be a strong family business with Miriam, Michael and Patrick actively involved in the business. Although he does not dare say it, you can see that he would be proud if any of them showed a willingness to follow him into what is a sometimes perilous but very fulfilling business.

At present the Cushendale Woollen Mills range includes blankets; throws for lounge and bedrooms; travel rugs and other fabrics used in homes and hotel interiors.

Its home furnishings come in a range of fibres, colours and sizes - Mohair (brushed and bouclé) - 100% Irish wool - lambswool and cotton Chenille. There are scarves, hats, ruanas (capes), pocket stoles and other fashion items. Recently the business has expanded into supplying the hand crafts sector with knitting and crochet yarns and felting wools.

The part played by the Duiske River in providing a clean water source is highlighted by Philip who explains that unlike over 55% of water supplies in Kilkenny which come through limestone making the water “hard”, water in the Duiske comes through or down from, Brandon Hill which is the final granite outcrop of the mountains ranging from south of Dublin giving the water coming down from there a pureness of quality and a softness important in the textile milling industry. The water is also used by many families for drinking purposes and it does taste pure.

Philip Cushen has a great respect for the past and for those who went before him. He has noticed that as time goes on he is selling more and more to people who can recognise and appreciate the value of a quality product and the story that goes with it. People want to buy something unique that will last and that looks different, distinctive and made by hand in Graignamanagh.

Philip Cushen has a fire than burns bright to produce things of beauty and excellence.”You are always trying to make something better than the last product, to set a higher standard,” he explained. “You must be fired up enough to always try to create something different, unique, something of which you can be proud,” he added.

Noble words from a man who is keeping a tradition alive which has an important place in our history and hopefully a place in our future.

Share this: